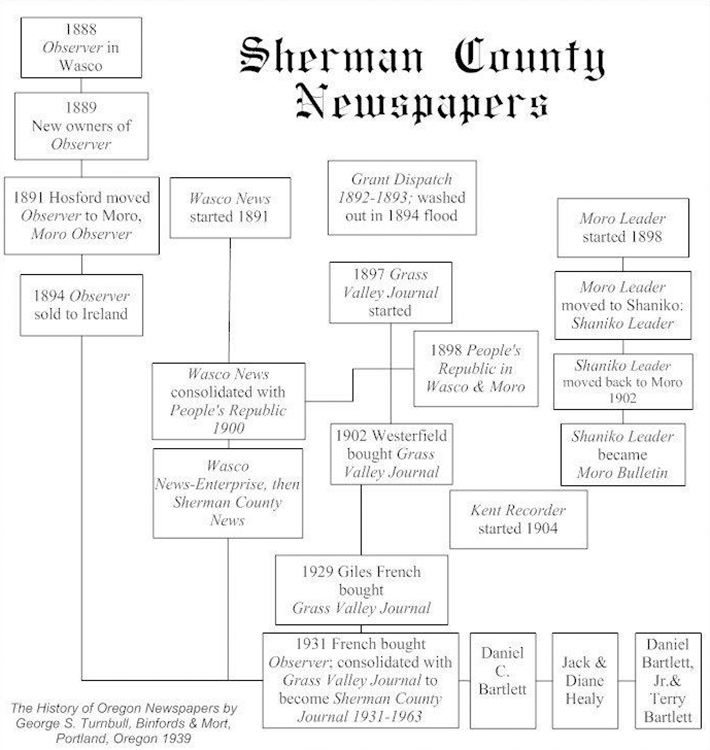

Sherman County Newspapers: In the Beginning

By Chris Sanders

In the beginning, Sherman County newspaper competition was fierce. Community citizens could go to bed one night and not know who would have control over their news the following day.

1888 – The Observer was founded in Wasco. Cornelius J. Bright in the fall of 1888 established the Wasco Observer, the first newspaper between the rivers, in the fall of 1888. The County was formed from Wasco County in 1889. In 1890 Bright was admitted to the bar and opened his law office at once. [Source: Resources of Wasco and Sherman Counties – The Dalles Mountaineer – Souvenir edition – published 1 January 1898] Bright’s obituary states that he sold the paper shortly after he established it. Giles French, in The Golden Land, stated, “Newspapers were started. After the Wasco Observer had been bought by Moore Brothers and moved to Moro, Dr. H.E. Beers financed the Wasco News with James W. Armsworthy and V.C. Brock as editors.”

1889 – The Observer taken over by new owners in Wasco.

1891 – The Observer was moved to Moro by John B. Hosford, becoming The Moro Observer. Giles French wrote, “At Moro the Observer prospered under J.B. Hosford with Clyde Williams as the printer until 1894 when it was sold to D.C. Ireland and sons, C. Leonard, and Francis C.”

1894 – The Grant Dispatch washed out in 1894 flood.

1894 – The Moro Observer was sold to DeWitt Clinton Ireland who died 1913. He was succeeded by his son C. Leonard Ireland.

1897 – The Grass Valley Journal was established and edited by Clark E. Brown. [Source: Resources of Wasco and Sherman Counties – The Dalles Mountaineer – Souvenir edition – published 1 January 1898] Giles French wrote in The Golden Land, “The enterprising citizens of Grass Valley needed a paper to give expression to their ideas of metropolitan promise and capitalized themselves for $2,000 in 1897 as the Grass Valley Publishing Co., with George Bourhill, J.H. Smith, William Holder, Charley Moore and J.D. Wilcox putting up the money to start the Grass Valley Journal. C.E. Brown was the editor at first and then W.I. Westerfield came up from Lafayette to take over, remaining until his death in 1923. His widow continued to operate it.”

1897 – The Wasco News. The first microfilmed copy is for 28 October 1897 and goes through to 17 January 1908. It may have lasted longer than that but, regrettably, no papers survived to microfilm.

Jas. W. Armsworthy first worked on the “Old Observer,” and after completing his mechanical knowledge in Portland, returned to Wasco in 1892. In November of that year, he purchased the plant of the Wasco News, and by adding a complete job department to it, has to-day (1898) a complete printing office in the county. [Source: Resources of Wasco and Sherman Counties – The Dalles Mountaineer – Souvenir edition – published 1 January 1898] While it is not clear how long Armsworthy operated the paper, the 1900 Sherman County census shows his occupation as a printer.

1898 – The People’s Republic started in Wasco 21 August 1898 and operated until 10 November 1898 when it was relocated to Moro starting 17 November 1898.

1898 – The Moro Leader started and a short time later was moved to Shaniko to become The Shaniko Leader. Giles French wrote in The Golden Land, “Not everyone was pleased with the Observer, however, the businessmen backed Leon W. Hunting in a new paper, The Moro Leader, which he edited for nearly a year before turning it over to Maurice Fitzmaurice. It was as Republican as the Observer, had less advertising and more editorials. William Holder, a one-time sheriff, bought it in April 1900, and moved it to Shaniko.”

1900 – The People’s Republic consolidated with the Wasco News becoming the Wasco News Enterprise Giles French wrote in The Golden Land, “The Populists were numerous enough to have their own newspaper and started the People’s Republic at Wasco… Grant Kellogg was editor after W.J. Peddicord got the paper on its way in 1898… and he moved it to Moro in a new building put up by J.M. Powell… The Observer was too strong for the People’s Republic and it soon returned to Wasco to perish by consolidation with the (Wasco) News…. The Irelands were left in possession of the county seat location….

1902 – Grass Valley Journal was purchased by Westerfield. He owned and operated it up to the time of his death 14 January 1924. His obituary states that he was the editor for 26 years and had relocated to Grass Valley in 1897 from his former family home at Lafayette, Yamhill Co., Oregon.

1902 – The Shaniko Leader moved back to Moro to become the Moro Bulletin.

1905 – The Kent Recorder started. Giles French wrote in The Golden Land, “The Kent Recorder was published for a time in 1905 by E.H. Brown and there was a paper briefly at Grant when a plant was brought over from Dufur for a few months.”

1927 – Sherman County News was operated out of Wasco. The papers on microfilm are for 19 August 1927 to 29 August 1930.

1929-1931 – Grass Valley Journal was purchased from Mrs. Westerfield by Giles L. French. The depression of that era had reduced all newspaper income until the county could not afford three newspapers. C. Leonard Ireland had succeeded his father on his death and was willing to sell. The Grass Valley Journal and the Moro Observer were consolidated in March 1931, with French as owner and editor. The next year he acquired the Wasco News which had had many editors and many owners. The consolidation was called the Sherman County Journal.

After Giles French retired, the Journal was published by Dan Bartlett, Sr., Jack Healy and Dan Bartlett, Jr.

2008 – Sherman County Journal equipment, machinery, and furnishings were sold to Sherman County Historical Society by the heirs of Dan Bartlett, Jr.

2010 – Sherman County Historical Society finished payment one year ahead of schedule!

2011 – Sherman County Historical Museum Team began work to exhibit part of this collection.

The Sherman County Journal

The Leading Sherman County Booster for One Hundred Years

Thursday, Sept. 14, 1989

Photos front page:

- Office of Sherman County Observer, D.C. Ireland at left, Fred Derby and C.L. Ireland. Photo courtesy of Mrs. Patricia Moore.

- Inside view of Sherman County Journal shop, about 1941. Giles French at left, Mrs. Ella Johnson at lino, Orval Thompson at right. Photo courtesy of Mrs. Patricia Moore.

Wasco Was Original Home of County’s First Newspaper

By Frederick K. Cramer

On March 6, 1931, Giles L. French’s first newspaper in Moro, the Sherman County Journal, appeared. The first issue of the newspaper combined the Sherman County Observer and the Grass Valley Journal into one publication. This was the first consolidation of newspapers in Sherman County since they were started by early settlers to print pioneer day events and to provide a local means of publishing homestead notices.

The Observer first appeared in Wasco on November 2, 1888, managed by C.J. Bright and A. B. McMillan. Fairly soon thereafter, the paper was published by J. B. Hosford, a pioneer attorney who dabbled in printer’s ink between cases. Although not a newspaperman by profession, Hosford wrote interesting news and overall, did a good job. There was no newspaper in Moro at the time and enterprising individuals believing that Moro would become the county seat, brought Mr. Hosford and the Observer to Moro. (Note: Sherman County was formed on February 25, 1889.) Hosford built a two-story building, living in the upper story and publishing the paper on the ground floor. During the Hosford ownership, he leased the paper to F. N. Bixby. This lease, from November, 1892, to January, 1893, was short-lived as Bixby quit after only two months.

As Hosford’s law business grew, he searched for a well-known newspaperman to take charge of the paper. Finally in June, 1894, he persuaded DeWitt Clinton Ireland, who had previously been connected with several newspapers elsewhere in the state, to take over, although it was to be November before Ireland and his two sons, C. L. Ireland and F. C. Ireland, would actually begin operating the paper. Arriving in Moro, Ireland eventually moved the newspaper out of the Hosford building into the McCoy building, which was the first business building built in Moro.

The Sherman County Journal occupies the same building today, although the building was moved a little further up the hill from its original location in November, 1901. It is still in this same block and faces the same direction as it originally did. Ireland and his two sons published the Observer for several years, with C.L. Ireland purchasing the interests of his father and brother in 1903. DeWitt Clinton Ireland died in 1913 and Roger T. Tetlow wrote a book about him entitled, The Astorian.

DeWitt Clinton Ireland was born in Rutland, Vermont in 1835. D.C., as his friends called him, founded his first newspaper at the age of 19 in Mishawaca, Indiana. Coming west during the Civil War, he searched as did many others, for free land, open country and unlimited opportunity. He settled in Portland, Oregon, where he worked for the Oregonian for a few years, and then moved to Oregon City, where he founded the Enterprise. In 1873, after spending several years on the Portland Bulletin, D.C. was ready to move to Astoria to found his most successful enterprise, The Astorian. Later, he also became mayor of that city.

In 1861, while first heading for the Oregon country, D.C. passed through The Dalles and while there, was asked to set up the first job press east of the Cascades in the Oregon country. The man who hired him was W.H. Newell of The Dalles Mountaineer. Ireland got the press going in a short time and Newell paid him enough money to outfit himself for his return trip back to the East.

In his farewell comments in the March 6, 1931 issue of the Sherman County Journal, C.L. Ireland observed that, at the time his father purchased the Sherman County Observer in 1894, D.C. was a confidential field man for Paul Mohr, a millionaire mining capitalist in Spokane who was interested in promoting barge and steamed services on the Columbia River and in building railroad short lines into the interior country from the river to provide freight for that river traffic and believed that a newspaper man would aid these endeavors. Paul Mohr’s brother, Gus, who was a county surveyor for Wasco County for a number of years after 1894, made the survey for a railroad south of Biggs to as far as Wasco. This railroad line, to be known as the Columbia Southern, was later built by E.E. Lytle and associates, using Mohr’s field notes after the panic of 1894 had taken a heavy toll of Paul Mohr’s fortune.

C.L. Ireland wrote that, during their residence in the county, the area grew from pioneer conditions to the (then) present condition of modern highways, a market road system, and a railroad serving all of its communities from north to south.

He stated that his paper had chronicled [the] family happenings to some extent of nearly every family in the county so that there were very few names of people in the county that he was not familiar with.

C.L. Ireland thanked everyone who had helped make the Sherman County Observer a real county, family newspaper and asked that the same helpfulness be given to Mr. French and the combination of two newspapers, the Observer and the Grass Valley Journal, to be known as the Sherman County Journal.

Earlier, a group of businessmen in Grass Valley had founded the Grass Valley Journal. Among them were George Bourhill, J.D. Wilcox, C.W. Moore and J.M. Smith. W.I. Westerfield purchased the paper in 1900 after managing it for three or four years for the company. After his death in 1924, Mrs. Westerfield operated the Journal until the paper was purchased by Giles French in 1929.

In his March 6, 1931 article announcing the merger of the two newspapers, Giles French said the Sherman County Journal is the official county paper, that it would contain official news of the county and the county court proceedings, as well as the general county news, and that it would continue the work of its parent papers in writing and editing the news from which history is made in Sherman County. This, Giles French did during the many years he retained ownership.

On October 1, 1931 he acquired the Wasco News Enterprise which made the Sherman County Journal the only county newspaper. On the 48th anniversary of the paper, Giles French wrote, “A newspaper is a part of life, a record of personal and public events, a means of community expression.”

The Sherman County Journal was published once a week; all subscriptions were mailed. A reporter in each town sent in weekly news items, with Giles also gathering stories himself, in addition to composing his editorials. Lela, Giles’ wife, did much work in the office, including running the linotype machine. Other linotype operators included Fred Derby, Ella Johnson, and Orval and Lutina [Thompson]. Patricia Moore, Giles’ daughter, recalled how she worked on the paper after school hours, on Saturdays and during summer vacations.

Giles French was also a representative in the Oregon legislature. He was appointed to fill an unexpired term in time to attend a special session of the legislature in 1935 and retained his status as a state representative until 1951. This busy man also found time to be a successful author of four published books. He authored, “These Things we Note,” a summation of his editorial columns; “The Golden Land,” a history of Sherman County; “Cattle Country of Peter French,” and “Homesteads and Heritages,” a history of Morrow County.

In 1963, Giles French sold the Journal to Dan Bartlett, the paper continuing under the same name at the same location. Giles continued to live in Moro. On June 27, 1976, Giles French died at the age of 81.

Dan Bartlett published the Sherman County Journal until it was purchased by Jack Healy in May of 1979, who took over the operation of the paper a few months later, in September. After shortly over a year of ownership, Jack Healy sold the Journal to Dan Bartlett, Jr., son of Dan Bartlett, the earlier owner. This last change was effective with the issue of October 9, 1980, the younger Bartlett becoming the new editor and publisher.

Sherman County Journal Still Uses Moveable Type

(unattributed)

Awe and excitement greet the arrival of a great invention, but when its usefulness ends, its passing often goes unheralded. Few people, for example, probably took notice the day the last merchant ship slipped into a harbor under sail, or the day the last steam locomotive roared down the tracks on a scheduled run.

Moveable type, one of mankind’s greatest inventions, is on the verge of disappearing after more than five centuries. Its demise has been almost overlooked amid the printing industry’s recent and rapid conversion to electronic technology. So forget, momentarily, the relentless march of progress. This is an obituary for an invention that literally changed the world.

Johann Gutenberg’s development, around 1450, of a practical way of making moveable type unleashed an information and communications revolution rivaled only now by the electronic computer. As recent as two decades ago, ink-stained oak cabinets containing drawers of type, were essential fixtures in any print shop, and it was every printer’s pride to have memorized which compartment held each letter. But when electronic photocomposition technology swept through the printing industry in the 1960s and 1970s most printers scrapped all forms of metal type. Today the old type drawers fetch $25 or $30 each in antique shops. In their place in the printing shops are chrome and plastic computer consoles with flashing lights and keyboards.

Simple concept.

Considering its impact on human affairs, moveable type is deceptively simple. A type is a small block of metal on the top of which is molded the mirror image of a letter, a number or a punctuation mark. Printers today usually call it “hand-set” type to distinguish it from metal type set by Linotype machine. This machine forms complete lines of type molded on the top edge of thin, metal “slugs.”

A half-dozen small U.S. foundries continue to turn out hand-set type that isn’t much different from that produced by Gutenberg. But their market is a tiny fraction of what it was, say, in the 19th century, when more than two dozen U.S. foundries flourished, supplying type for the then-burgeoning number of newspapers and book publishers.

At Acme Type Foundry in Chicago, sales to newspapers, “are virtually zero,” says Richard Leipsieger, president. But Mr. Leipsieger refuses to concede defeat, and is ever on the lookout for new markets. “Moveable type isn’t dead yet,” he insists, noting that the foundry does about $250,000 a year selling to hobby printers and rubber stamp makers who use the type to make molds. “We also sell a fair amount of Spanish accented type for handbills and small Spanish language papers,” he says.

Out of Use.

Today, fewer than 2% of the nation’s newspapers and “job” printing shops are believed to use any form of metal type, whether set by hand of by Linotype. “We haven’t had any hand-set type for years,” says Daniel Hinson, The Wall Street Journal’s news production manager. A spokesman for the New York Times, one of the last major newspapers to switch to the new photocomposition technology, says all appurtenances of metal type, including moveable type, were packed up on July 4, 1978, and shipped to a museum at the Rochester, N.Y. Institute of Technology.

As recently as a decade ago, a handful of small newspapers and printers still eschewed even the Linotype, continuing to rely entirely on moveable type. No one in publishing circles seems to know whether any of these hand-set newspapers are left today. “I was told once there’s one somewhere in West Virginia, but I Don’t know if that’s true or not,” says Elizabeth Harris, curator of graphic arts at the Smithsonian Museum of American History in Washington. “If you find one, let us know about it,” adds an executive of the National Newspaper Association in Washington.

One of the last probably was the Round Rock Leader, a small weekly published since 1878 in Round Rock, Texas, just north of Austin. Mary Kavanaugh, the former owner and publisher, says she spent 45 of her 74 years standing in front of a case of moveable type plucking the letters out one by one with her right hand and depositing them in a small metal tray, or compositor’s “stick,” held in her left hand.

Photocomposition is cheap and fast; a typographer can “set” an entire newspaper page in the time it would take to set a paragraph or two by hand. Images of each letter, stored as electric impulses in a computer-like machine, are flashed onto light-sensitive paper when the operator tapes a keyboard. The developed paper, carrying complete columns – or even pages – of type, is then used to etch a metal plate that goes onto an off-set press for printing.

Even though it is now all but obsolete, few inventions in history can match moveable type in their impact on human events. Until the middle of the 15th century, printing was a limited art. Textile designs, playing cards and short religious tracts were occasionally printed form wooden blocks on which the design or text was tediously carved by hand. Books were thus an expensive rarity, available only to the literate few among the clergy and gentry.

Origin of the Species

Historians still debate where and when the idea of moveable type arose. The Chinese did some printing from moveable Chinese characters in the 14th century, and a Chinese type foundry was operating in Korea in the late 1300s. In Europe, several attempts to produce moveable type were made in the early 1400s, but none proved practical.

Then, sometime in the 1440s, a former goldsmith in Mainz, Germany, developed an adjustable mold that produced type identical in all dimensions except width, a trick that had eluded others. Johann Gutenberg’s type fit together snugly, produced straight, even lines of letters and left uniform spacing between letters.

Despite his efforts to keep the mold a secret, Gutenberg’s invention spread rapidly. The ability to cast each letter in metal, which could withstand the pressure of the press and could be reused hundreds of times, turned printing into one of the world’s first industries to use mass production. By 1600 according to some estimates, between 15 million and 20 million volumes of 40,000 books had been printed. Literacy exploded, new ideas spread rapidly and the arts and sciences flourished. For more than four centuries, moveable type was the primary tool by which humans recorded and disseminated knowledge.

In the U.S., use of moveable type paralleled the growth of the newspaper business, reaching its peak in the late 1880s. The foundry that has dominated U.S. type-making for 85 years is American Type Founders in Elizabeth, New Jersey. ATF was formed in 1892 as a near-cartel to save type foundries from a technological disaster. Eight years earlier, a Brooklyn inventor named Ottmar Merganthaler had patented the Linotype machine. A Linotype operators punching a keyboard could set type several times as fast as a typographer could set moveable type by hand.

Foundries Consolidate

Newspapers readily adopted the Linotype for their text type, retaining the moveable type only for headlines and display advertising. The foundries, their biggest market lost, banded together and formed ATF, a move that put the bulk of the nation’s type-making under one roof.

ATF mechanized the manufacture of type, which hadn’t changed much since Gutenberg’s day. With the market for text type gone, ATF concentrated on advertising type. Its designers organized the hodgepodge of typefaces into distinctive “families,” such as Century. Old, forgotten styles were revived and new ones developed. The foundry’s efforts gained quick approval by the newly emerging advertising agencies. The esthetic aspects of type became a key part of graphic arts.

The ATF foundry today is little different than it was in 1900. It is housed in an old red brick building in Elizabeth, an industrial city on the outskirts of New York. But while it once owned and occupied the entire building, it now is relegated to a leased corner of the third floor. Here, still lined up in rows, are 99 of the automatic type-casing machines it had built in the late 1890s. Banks of file cases and cabinets hold thousands of type patterns, matrices for the molds and type samples dating back to the turn of the century.

As recently as the 1960s, the foundry employed 200 people and turned out a million pounds of type a year for the nation’s printers. It could supply complete fonts of any one of more than 3,000 type faces. Today, it employs only 25 people, all but two of whom are over age 50. “When these old-timers pass away, we won’t be able to replace them,” says George Gasparik, the 63-year-old foundry manager who started here as a teen-ager in 1938.

Today’s Uses of Type

Mr. Gasparik won’t disclose the foundry’s current production. But fewer than a dozen of its type-casting machines now operate at any one time.

The foundry’s biggest customers these days are manufacturers who still use moveable type to print their labels and product identification tags.”There’s also a cult of older printing teachers in the schools who love to have the students set type by hand,” adds Richard Bryan, president of the ATF-Davidson division of White Consolidated Industries, which owns the foundry. Both these markets are declining, Mr. Bryan concedes.

Yet ATF-Davidson doesn’t plan to close the foundry. “It’s a nice little cash job and we’re happy with it,” Mr. Bryan says. “Obviously, no one else is going to get into the market.” The foundry’s only significant competitor is Castcraft Industries, Inc. in Chicago, he says.

One possibility for the future, Mr. Bryan says, is for ATF to move into the European market where a German foundry still does a brisk business in moveable type. “Another possibility is to go into the novelty gift business, where you might give a person a gift of his name in type for a birthday,” he suggests.

Mr. Gasparik, for one is confident that after 500 years moveable type hasn’t completely outlived its usefulness. “There’ll always be a need for type,” he says.

Giles French

“Mad is a temporary thing,” said Giles French. “If you’re worth your salt in this business you’ll have plenty of people mad at you. But if you go around trying to be a doormat and a nobody, somebody will sure as hell help you.”

Giles French served as editor and publisher of the Sherman County Journal in Moro as well as in the Oregon State House of Representatives from 1937 until 1951, plus one special session. During that time he took them all on – big and small. And a good many times he won.

Giles French’s Career of Wit Spans 50 Years

July 15, 1976

By Rep. Roger Martin

“His is the philosophy of a sage, cast in proverb form, with flashes of humor to illuminate his thought.”

These words were spoken by the late Gov. Charles Sprague about Eastern Oregon’s Giles French, who was laid to rest last week in his beloved Sherman County.

French was best known as a country editor who did his own thinking. But he was also a laborer, farmer, stockman, clerk, legislator and historian.

His writings, spanning the past 50 years, will be a living legacy to a man who was a big as the big country his loved. And many of them take on added meaning in our 200th year as a Republic.

Here are some samples of the Giles French wit and wisdom:

“There is, in any organized society, a shortage of men willing to evolve a theory or take a stand and readers and listeners react to them favorably. Such men clear the air, provide a basis for decision and are respected…”

“… we have been told that a few hastily passed laws would make everyone happy, provide for the underfed, underclothed, under privileged, under washed and underdog, and lead us to a day of peace and security beyond the dream of an economic royalist… Is it possible that people are going to have to take a hand in preparing their own happiness>”

“There is little evidence to show that people are winning their battle for more freedom. Whatever security they have been given has been at the price of part of their freedom… During 1946, therefore, this newspaper will endeavor to speak for the people, for their freedom. Let them obtain their security from the exercise of that freedom, not as a gift from the government.”

“No man knows enough to govern other men… that is why we have this system. It gives us a check on those who have not yet learned that no man knows enough to govern others.”

“The easier we make it for the weak to escape responsibility for the results of their weakness, the more weak people we will have. As a nation we are making far too many excuses for ourselves.”

“There is no limit to things people will think they need if someone else will pay for them.”

“Early in the session the chaplain prayers for the legislators, that they might have strength and wisdom and character. Later the chaplain will pray for the people.”

“There is no way for the government to do something for the people without doing something to them at the same time.”

“No wonder socialists like government ownership. They couldn’t hold a job under any other system.”

“A government that protects the weak will always have lots of that kind of people; a government that lets the strong develop will have that kind.”

“This generation seems to expect the government to do more for it than the passing generation expected to do for itself.”

In commenting on the death of several others, Giles French put to paper words which may describe our feelings at his passing.

“The death of Jim Coleman leaves one fewer of that group of Americans who were guided by conscience alone.”

“When the spirit of any of us ventures beyond this mortal coil, something goes out of the life of those who remain and occasionally such a passing seems to definitely terminate an era.”

And, a statement of his which could well provide an epitaph for Giles French reads thusly, “Maybe it isn’t that the last frontier is gone, but the last frontiersman.”

So long, Giles French. We’ll miss you.

Eugene Register-Guard, June 29, 1976

Giles

Oregon lost one of its 24-karat, diamond-studded personalities Sunday when Giles French died. Giles (nobody ever called him Mr. French) was an influential legislator for nine terms and editor of the Sherman County Journal at Moro, one of the really sprightly weekly newspapers in the state. But his main contribution was himself. There just wasn’t anybody else like him.

To say that Giles was a conservative would be to understate his convictions. Even reactionary does not describe him. He wanted to keep government out of people’s lives. When he sat in the Oregon House of Representatives, the clerk would call the roll – Dyer, Eaton, Erwin, Farmer, Fisher, Francis – and record the “aye” votes. The next name was French. And the vote was usually a resolute “nope.”

Giles knew, absolutely knew, that country people were smarter than city people and ought to keep control of things. He distrusted intellectuals, although in some ways he was one himself. Once, O. Meredith Wilson, president of the University of Oregon, delivered an especially brilliant speech. On the way out, a fellow editor asked, “How did you like that, Giles?” Giles replied with a single bad word.

His paper was widely read beyond Sherman County by readers who recognized the greatest Oregon writer of single paragraph commentary since Clark Wood of the Weston Leader earlier in the century. He was a substantial historian. His biography of Pete French, the cattle baron (no relation), stands by itself.

He was gruff and ascerbic with his cattleman’s hat and stogey. But he didn’t let his politics interfere with his friendships. For example, he was very fond of Maurine Neuberger, with whom he served in the House, although the two disagreed on almost everything. He could be delightful and maddening at the same time – and he knew it and gloried in it.

The eastern part of the state has produced a number of personalities who could have lived nowhere else. Giles well may have been the giant of them all.

The Dalles Chronicle, April 27, 2003

Compiled by Elroy King

40 Years Ago, April 27, 1963

Giles French announced this week in the Sherman County Journal at Moro (Oregon) that he and his wife are selling the newspaper which he has published since 1931 to Dan C. Bartlett of Hermiston (Oregon). Bartlett has published the Herald for 15 years and French said Bartlett’s son, Dan Jr., will be associated with his father soon in the newspaper business.

Sherman County’s first newspaper was the Wasco Observer, published by C.J. Bright and R. B. McMillan. The purpose was to do the printing for the new county and to carry other business incidental to the county seat’s development. The proposed county had a population of 1,400. The first issue came off the press on November 2, 1888. When Bright became county school superintendent, the paper was edited by D.C. Ireland, then sold by McMillan to J.B. Hosford in February 1890 who moved it to Moro in 1890.

Dr. H.E. Beers and J.M. Cummins launched the Wasco News in July 1891. They were followed by Frank Bixby and the jovial and popular James W. Armsworthy. V.C. Brock became a partner in October 1897 and the paper was increased to eight pages. In 1899 it came into possession of Lucius Clark and A.H. Kennedy, then Norman Draper took over with Brock as editor. Within the next year and a half, the paper had three sets of publishers: A.S. McDonald, Pound & Morris; G.E. Kellogg, J.W. Allen & M.P. Morgan 1904; Mr. Allen, sole proprietor 1904; Day & Walker 1907 and R.R. Flint 1909. In 1910 the News is listed as the News-Enterprise, apparently consolidated with another newspaper. Successive editors were Blodgett, Pierce, Snider, Anderson, and Adsit who changed the name back to the Sherman County News. In 1930 Anderson was back, followed by Robinson and McCall who sold to Asa Richelderfer, after which the News was acquired by Giles French in 1932. French consolidated it with the Sherman County Journal at Moro.

Moro’s first newspaper was the Observer, moved from Wasco in 1891 by Hosford. In June 1904, veteran journalist D. C. Ireland and his sons purchased the Observer, which he published until his death in 1913. Dissatisfaction with the Observer by some businessmen led to the 1898 launch of the weekly Leader by editor L.H. Hunting, followed by M. Fitzmaurice who moved it in April 1900 to Shaniko where he launched the Shaniko Leader. Briefly, three other newspapers served the little town of Moro: The Observer, The Moro Leader and The People’s Republic. The Moro Bulletin was published briefly by Mr. Holder in 1902.

The Observer was published by Giles L. French of the Grass Valley Journal in 1931 and the papers were consolidated as the Sherman County Journal. French also took over the Sherman County News from Asa Richelderfer and changed the name back to Wasco News-Enterprise. The News-Enterprise was consolidated with the Journal on March 4, 1932.

The Grass Valley Journal was launched on November 12, 1897 by the Journal Publishing Company with C.E. Brown, editor, after which the Grass Valley Publishing Company formed with C.E. Brown, George W. Bourhill and J.H. Smith as incorporators, and William Holder, C.W. Moore and J.D. Wilcox as stockholders. W.I. Westerfield did not found the Grass Valley Journal but operated it longer than all others combined. He edited and published the Journal until his death in 1923, and the paper was continued by his widow until she sold to French in 1929.— Bartlett Sr, Healy and Bartlett Jr.

FACT CARD:

Giles & Lela French

Giles French was born in 1894 to Rosa (Maricle) & Leroy Ransom French, followed by his sister Beatrice in 1896.

___: WWI

In 1919 Giles married Lela Barnum

They had four children:

- Jane

- Wyman John 1922-1945

- Clinton Barnum 1920-1931

- Patricia R.

1929: Giles French purchased the Grass Valley Journal in October, 1929. “Westerfield [widow of the Grass Valley Journal publisher] came in one day, almost tearful, and asked me if I wouldn’t buy her out. She couldn’t handle Fred [Derby] and she was too moral to condone his drinking. She wanted $1,500. I gave her a check for $100 and took over the Grass Valley Journal, agreeing to pay so much a month. That was on October 1, 1929. Before that month was out Wall Street had collapsed, prices had dropped and the big depression had begun.” ~ Giles L. French.

1931: Giles and Lela French purchased the Sherman County Observer. It was the first consolidation of county newspapers. “So I went down to Moro and talked to Leonard Ireland. He wanted to sell. We made a deal. I think it was $3,500.” ~ Giles L. French

1931: Giles and Lela French moved their family to Moro. “We had moved to Moro the last days of February 1931 and Clint was dragged by a horse and killed that May. People were kind; in fact it is my recollection that people were almost invariably kind…” ~ Giles L. French

1932: Giles French, acquired Asa Richelderfer’s Wasco News-Enterprise, and the Journal was the only newspaper in the county. “His is the philosophy of a sage, cast in proverb form, with flashes of humor to illuminate his thought. ~ Governor Charles Sprague

1935-1951: Giles French represented this district in the Oregon legislature.

1945: March 1, 1945, Salem, Oregon. WE REGRET TO INFORM YOU… WYMAN JOHN…KILLED IN ACTION…

___ : Founder of the Sherman County Club

___ : Mayor of Moro for 20 years.

___ : Published The Golden Land…

___ : Published Morrow County History

___ : Published Peter French, Cattleman

___ : These Things We Note

1976: “Giles French, dead at 81, was a personality none who knew him will forget. To know him was not necessarily to love him. He had a sharp tongue and a rural arrogance which tended to infuriate city dwellers, at least on first meeting. Yet his intimate knowledge of state government, particularly taxation, and his wit and erudition made lasting friends.” ~ The Oregonian, July 1, 1976.

[from the Giles French autobiography in SC: FTR:]

Mrs. Westerfield came in one day, almost tearful, and asked me if I wouldn’t buy her out. She couldn’t handle Fred and she was too moral to condone his drinking. She wanted $1,500. I gave her a check for $100 and took over the Grass Valley Journal, agreeing to pay so much a month. That was on October 1, 1929. Before that month was out Wall Street had collapsed, prices had dropped and the big depression had begun. What a time to start a business, little or big. It became apparent that the Grass Valley Journal… was not going to be enough to make a living for a family of six. So I went down to Moro and talked to Leonard Ireland. He wanted to sell. We made a deal. I think it was $3,500 I was to pay him, that being his debt to the church and I was to get a loan on the building for $1,500 from the veteran’s loan of the state. I also assumed some of Ireland’s accounts around town, which I think came off the building loan. I still owed Mrs. Westerfield some money. Ireland kept his linotype although it remained in the office for some months until he had located at Molalla and Mrs. Arthur (Ella) Johnson operated it.

We were very poor, were very much in debt, a depression was on and there was no money in circulation. As a lesson in practical economics it was the best possible and I have since been thankful for it but without having any desire to repeat it. We had moved into the big white house belonging to Lela’s parents and our meager stock of furniture wasn’t near enough to make it look lived in, let alone comfortable. We had no automobile.

But things got better, mainly perhaps because they could not get worse. We had moved to Moro the last days of February 1931 and Clint was dragged by a horse and killed that May. People were kind; in fact it is my recollection that people were almost invariably kind…

When Ireland moved his linotype out, we bought an old Model 10 from a newspaper in Clatskanie. It cost about $500 as I recall…

The City of Moro was in terrible shape financially and citizens didn’t like the men who had been running it. Being a new man in town, I was elected mayor, both sides thinking apparently that I wasn’t directly allied with the other. Both were right. It turned out to be a twenty year job.

When we took over the Sherman County Observer there were four paid up subscribers. The others were all delinquent and many were so mad at old Ireland they had told him to discontinue the paper. All this made new owners welcome and many came to say that they would be glad to continue the paper but few had the $1.50 required.

There was almost no advertising except an occasional ad from The Dalles. But the cigarette companies carried large ads, big fine ads that were very welcome, the local power company had smaller ads and consistent, there were still a few homestead notices, the county had to publish its court proceedings and there were lots of foreclosures of farms that paid a stated fee. We lived and made regular payments on our debts.

The newspaper caught on and was welcomed. Newspapers in Sherman County had always used ready print, that is, bought two of their standard four pages from the Western Newspaper Union already printed with some feature material and some Oregon news and some ads… Because the Sherman County Journal, which was the name I chose for the consolidation of the Grass Valley Journal and the Moro or Sherman County Observer, was to have the news formerly carried by two newspapers I decided that I would have a four page newspaper.

This required much more writing and searching for interesting local stories about which to write. The experiment station was a fine source and Dave Stephens, the superintendent, was anxious to have someone disseminate the results of experiments he was conducting. I discovered that many citizens did not know the functions of county officials nor even of the place county government in general had in the scheme of things; there was a controversy going about the operations of the road department.

There was something to write about. Even the geography of the county was not well known, nor were citizens acquainted about their own county for while there had been automobiles for fifteen years, the roads were not very good. Schools were just being consolidated by bringing rural school children into the five towns but the prejudices were far too great for any consolidation of schools in town.

~ Me, An Autobiography of Giles French, Sherman County: For the Record.

(unidentified newspaper) August 2, 1963

Local Publisher Sells County Paper

French Serves Community 32 Years

Giles L. French, publisher of the Sherman County Journal for the last 32 years, amazed the local residents by announcing the completion of an agreement of sale May 1 with Dan Bartlett. Prior to the newspaper consolidation in 1931, Mr. French published the Grass Valley Journal. A noted columnist and editorial writer, his column, These Things We Note, is often quoted by the McCall’s magazine and newspapers throughout the state.

Mr. French served as a representative in the Oregon legislature from 1937-1953. He filled an appointment in 1935, then was elected for eight consecutive sessions and one special session concerning the rebuilding of the capitol which had burned in 1935.

When asked what he stood for as a representative of district 22, he replied in his typical ironical manner, “Much less than anyone else.” He quickly added, however, that he opposed the growth of government which was faster at that time than any other period in history.

As author of The Golden Land, Mr. French has succeeded in publishing a very readable account of Sherman County history. He is presently involved with a factual account of cattleman Peter French. It deals with a Harney County rancher who incidentally is not a relative.

“These Things We Note will be continued,” confessed Mr. French, “until I am fired.”

The Sherman Hi Times appreciates this opportunity to pay tribute to the veteran editor, Giles French.

(Reprinted from the Oregonian, written by staff writer, Peter Tugman.”

“Mad is a temporary thing,” said Giles French. “If you’re worth your salt in this business you’ll have plenty of people mad at you. But if you go around trying to be a doormat and a nobody, somebody will sure as hell help you.”

And French ought to know. He retired recently after 32 years as editor and publisher of the Sherman County Journal in Moro… [He] served in the State House of Representatives for 15 years from 1937 until 1951, plus one special session.

During that time he took them all on – big and small. And a good many times he won. It would be a shame if his voice and the weight of his opinion were lost with his sale of the Journal. To some extent they won’t.

He has written and published one book, The Golden Land, a history of Sherman County, has completed another on Peter French (no relation), the pioneer cattleman. And he is contemplating still another book because, “These are the things I’ve seen and experienced and it would be a shame not to record them.”

And it would be a shame if someone does not record Giles French while he can be “seen and experienced.” It would be an unsettling experience to the students, surely, if he could be persuaded to give a series of lectures to journalism students on country editing. But it would be a valuable one, for he is not a product of the journalism school and belongs to a species of newspaperman which is vanishing like the African Aryx.

Bucking like a steer, he refused to be interviewed, finally consented to be photographed, but happily sat down to chat. And the result was a series of reflections and short pungent aphorisms on everything from women, newspapering and politics to social theory.

On the newspaper business; “I guess I just gravitated into it. I was a wheat farmer and I hung around the newspaper office whenever I had any spare time.”

“I never had any formal training. I went to the university (of Oregon). But I majored in English, law and history. I’m inclined to violent disagreement with the journalism school theories. Why not take something that’ll do you some good?

“History and law are valuable. But literature – there is nothing more interesting than literature. All the wisdom, philosophy and lore of living is in literature. And you don’t need to have some professor banging your eardrums to appreciate it. You can buy Plato for four bits in a pocketbook.

“Newspapers. There is no place in the community where a man can exercise so much influence. Or even control. Course you know if you don’t do a good job, you’re damn soon out of a job.

“People check up on politics every election year. But on a newspaper it’s judgment day every Thursday. I guess for you fellows is comes every day.

“I don’t know of any place you can run out of friends quicker than on a newspaper… or any place where you have a better chance to help people. I always had my desk just inside the door. I found people were willing to forgive my foibles when they thought I was trying to do the right thing. People respect reasonableness.

“They’ll even forgive bad writing. God knows I’ve foisted enough on the public in 30 years. I think the writing in newspapers nowadays is one hundred percent better than it was 30 years ago. I think good writing is largely a matter of continuous work. And the right goals. It should be easy to read, easy to understand and simple of construction.”

On social theory: “We cannot continue to consolidate into big centers and retain the interest and strength of the little people who count. Our strength is in the people who cut the logs, raise the beef and plow the fields, not in people who pound the typewriter like us. That’s just froth.

“I’m for ending consolidation right out in the sticks.”

French has lost, for the present, his fight to re-apportion the State Legislature, allowing one senator for each county. The Oregonian opposed the plan on the grounds it would give disproportionate weight to rural sections and discounted French’s theory that counties ought to have equal representation in the legislature as political units of some sovereignty.

“That’s a specious argument,” said French. “In the first place the states are not sovereign, but only exercise residual powers. The counties would have some of the same options under the home rules charter plan.

He thinks regions, such as Eastern Oregon, or the desert counties, or the farming areas ought to have a voice, as such in legislature because they represent ‘a community of interests.’

He also has a distrust of the big cities and a belief that the strength of the people is diluted as they gather in big cities to work or creep home at night to bedroom neighborhoods with no real community of interests.

“Goldsmith said it all,” said French, “ ‘Where wealth accumulates and men decay.’ “ [The Deserted Village by Oliver Goldsmith]

“I guess I’m just a damn radical. Of course in the modern use of the term liberals would say I’m a conservative. I add two and two and get four. To be a liberal nowadays two and two has to equal five.

“The term liberal has been perverted these days to mean a person who believes in big government. This is just the opposite of the real meaning of the term which derives from the Greek word “librus” meaning “free” – freedom to act with only those restraints necessary. This is not big government.”

Offer Draws Scares

Here is French in action on big government, writing in 1962 to decline with hauteur a proffered government loan of $8,500: “Sherman County has been declared an area in need of redevelopment and entitled to federal loans and grants because of insufficient income and above average unemployment. Sherman County of all counties. Sherman County that usually has the largest per capita income of any county in Oregon and is always among the most prosperous in the nation; Sherman County, whose citizens bought more E bonds per capita than any other county… Sherman County is depressed?

“It is not so.

“… What becomes of a nation when even the rich beg? … It may be politically wise to distribute some federal money just before an election… but… it certainly is not wise to force it on communities that do not need it and should have too much honor to accept it.”

Attitude ‘Boot’

That is not only looking the gift horse in the mouth. It’s also giving it a sharp boot in the slats. And the measured grandness of the prose would be hard to match.

Will French’s old typewriter be silenced and locked away not that he has sold his paper, or will he continue to volley and potshot at government, big daddyism?

“I’m 68,” he said, “and that’s too damn old.” Then he chuckled. “I suppose a fella, out of respect for his past ought to keep some of his bad habits.”

(undated clipping)

The Lake County Examiner, Behind the Sagebrush Curtain

by Leslie Shaw:

If we didn’t have a Giles French in Oregon we would have to invent one; but we do have and he voluntarily does a better job of being Giles French than all the rest of us put together. He’s the sage of the Moro Wheat Country and certainly one of the best known and respected newspapermen in all the state. For sure he’s one of my own favorites and I don’t use that expression lightly in regard to my fellow hacks.

Giles used to publish the little Sherman County Journal at Moro, and although he sold the paper to D.C. Bartlett, he still writes the weekly editorials and his widely famed Front Page personal column, These Things We Note. The latter each week is a series of one-paragraph observations about the passing scene… often barbed, often wise, often complimentary, sometimes humorous, always to the point.

I once heard Giles French tell a dinner audience that he himself believes the editorials to be more important than his TTWN column of paragraphs. But obviously both are well received, for they are widely quoted by other papers…and perhaps the TTWN notes are more widely quoted because a single idea, briefly expressed, is easier to hang onto.

A few months ago, Old Oregon, the alumnum magazine at the University of Oregon, published a fine article about Giles and his commentaries, quoting many, and now comes a whole entire book of French’s writings, covering 35 years of his Sherman County newspapering. Published November 28 by Binfords and Mort, 2505 S.E. 11th Ave., Portland, Oregon ($4.95), the book carries a fine introduction by the dean of Oregon newspaper publishers, Gov. Charles Sprague of the Salem Statesman.

A few quotes.

“The first Adam splitting gave us Eve, a force which man has never gotten under control.”

“Give a man a few crumbs and he will appreciate them. Give him cake and he will complain about the flavoring.”

“Man has never been very smart about prophesying the future; he draws it to suit his prejudices today.”

“A liberal is one who is anxious to trade any money for his political future.”

“You can’t improve a herd without selling off the culls and you can’t improve a society by encouraging the lazy.”

Giles French has written two earlier books, one about the wheat country of Sherman County and one about the early-day cattle baron, Pete French (Cattle Country of Peter French, Binfords and Mort, $3.50).

As the publisher stated on the dust jacket of Giles’ new book (which incidentally is title the same as his personal column, These Things We Note): “Perhaps no one will read this book cover to cover. It isn’t a narrative… This is not an expression of the philosophy of a moment or a year, but of a lifetime. It is not a book to be swallowed, but savored.”

I congratulate Giles French on his new book, and to show him how high an honor it is I’ll point out that no one has ever suggested a book of my writings.

Giles French Park, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Popular with fishermen, the park downstream from the John Day Dam is named for Giles L. French, Sherman County Journal publisher and editor, author and legislator. The son of LeRoy and Rosa (Maricle) French, he grew up in the Grass Valley area. He and his wife, Lela Barnum, were parents of Clinton, Patricia, Jane and Wyman. ~Me: An Autobiography by Giles French, Sherman County: For The Record.

Giles French Books

1958

French, Giles. The Golden Land: A History of Sherman County, Oregon. Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 1958. Notes, appendices. 237 pages. A thematic history of Sherman county based on oral histories. Topics include settlement, Native Americans, schools, towns, and industry. No table of contents is provided. Notes located at the end of each chapter are discursive and do not include sources.

1964

French, Giles. Cattle Country of Peter French. Portland: Binfords & Mort, 1964. Maps, photographs, illustrations, Index.

1966

French, Giles. These Things We Note. Portland: Binford and Mort, 1966. Quotations from the column of the same name and selected editorials published in the Sherman County Journal from 1931-1966.

1971

French, Giles. Homesteads and Heritage: A History of Morrow County, Oregon. Portland: Binford & Mort, 1971. Maps, photographs, illustrations, Index. 127 pages. A brief and general history of Morrow County from the Native American inhabitation through the 1960s. Chapters are arranged chronologically from Euro-American explorers through the 1950s and 1960s. Material was compiled from primary and secondary sources.

1983-1985

French, Giles. Me: An Autobiography. Sherman County: For The Record, Vols. #1-2 through #3-2. Sherman County Historical Society, Moro, Oregon.

Oregon Newspaper Hall of Fame

“No man knows enough to govern other men… that is why we have this system. It gives us a check on those who have not yet learned that no man knows enough to govern others.” – Giles French